![]()

Redefining Refugee City

Spring 2020

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Speculative City Seminar

Location

Rohingya Refugee Camp, Kutupalong, Bangladesh

City Scale

Critics

David Eugin Moon

Type

Analytical Study

Designing for refugees is one of the most sought after trends followed by many architects and designers. They have an affinity for designing tech heavy, modular, “one size fits all” solutions for a group of people who couldn’t be more different from them. There has been so much focus on the speed and ease of construction for these “camps” that designers have forgotten the basic humane aspects of “living”.

Most of the world’s refugee camps are designed as temporary facilities and designers have not focused on the journey and mental health of the refugees for whom they design for, therefore this booklet speculates on the need to Redefine the Refugee City as a vibrant city, with thriving economies, judicious system of governance and civic institutions and a step away from seeing them as temporary camps or settlements.

It is critical for us to study and respond to the socio-cultural ramifications of migration. How do we stop seeing these “refugee settlements” as “camps’ ‘? How do we use ‘materials’ and local partnership to create a sense of identity and ownership for these migrants? How do we build cities that are adaptive to the needs of these ever changing dynamics? How do we ensure that host communities absorb refugees and migrants into their local social fabric?

Most of the world’s refugee camps are designed as temporary facilities and designers have not focused on the journey and mental health of the refugees for whom they design for, therefore this booklet speculates on the need to Redefine the Refugee City as a vibrant city, with thriving economies, judicious system of governance and civic institutions and a step away from seeing them as temporary camps or settlements.

It is critical for us to study and respond to the socio-cultural ramifications of migration. How do we stop seeing these “refugee settlements” as “camps’ ‘? How do we use ‘materials’ and local partnership to create a sense of identity and ownership for these migrants? How do we build cities that are adaptive to the needs of these ever changing dynamics? How do we ensure that host communities absorb refugees and migrants into their local social fabric?

When we look at the current situation, there are more refugees and internally displaced people today, than at any point since World War II. People all over the world are driven from their homes by conflict, persecution, environmental calamity, or dire economic straits. They have been deprived of their claim at land, statehood, material possessions, and even their loved ones. More than half of these refugees are children, who with their families seek solace in purpose-built “refugee camps” and unplanned settlements, where they wait out their displacement, with an attempt to begin a new life. While their numbers are increasing each year, the average stay in a refugee camp is currently around seventeen years, and yet it keeps increasing year after year. Furthermore, this situation is going to get worsened by the current Climate crisis which has increased the number of climate refugees migrating to safer lands.

When we look at some of the refugee camps currently in the world, we see how there are many kinds of settlements, from camps set up by refugees themselves, in which case they have lesser facilities and organizations, or camps set up by agencies such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These camps are more ordered and have more amenities for people. There is also a distinction made based on the governing body over a settlement. Some camps or parts of them might fall under the UNHCR, but there are many that are controlled by host communities (Host communities are communities native to the area that the migrants have settled in).

More factors that affect the fabric of a camp are the number of displaced persons seeking refuge, the cultural and ethnic ties between the host country and the refugees, the host country’s capacity to absorb new people, and the military and political circumstances of the host country are all factors that contribute.

Apart from the usual ‘to be expected’ modular cramped, temporary shack construction seen in the typical camp, there are many new age variants designed keeping in mind the refugee and their mental and social needs. Maidan Tent by Bonaventura Visconti di Modrone and Leo Bettini Oberkalmsteiner aims to create a semi open indoor public communal space with adaptive features to protect from water, wind and be fire resistant. The garden library in Levinsky Park in Tel Aviv, Israel caters to the migrant population that congregates there. It is constructed to be open to all, a conscious decision to ensure free and equitable access to the library. Playgrounds for Refugee Children in Bar Elias, Lebanon by CatalyticAction was created as an effort to address the psychological trauma experienced by migrant children and to ensure their healthy development.

When we look at some of the refugee camps currently in the world, we see how there are many kinds of settlements, from camps set up by refugees themselves, in which case they have lesser facilities and organizations, or camps set up by agencies such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These camps are more ordered and have more amenities for people. There is also a distinction made based on the governing body over a settlement. Some camps or parts of them might fall under the UNHCR, but there are many that are controlled by host communities (Host communities are communities native to the area that the migrants have settled in).

More factors that affect the fabric of a camp are the number of displaced persons seeking refuge, the cultural and ethnic ties between the host country and the refugees, the host country’s capacity to absorb new people, and the military and political circumstances of the host country are all factors that contribute.

Apart from the usual ‘to be expected’ modular cramped, temporary shack construction seen in the typical camp, there are many new age variants designed keeping in mind the refugee and their mental and social needs. Maidan Tent by Bonaventura Visconti di Modrone and Leo Bettini Oberkalmsteiner aims to create a semi open indoor public communal space with adaptive features to protect from water, wind and be fire resistant. The garden library in Levinsky Park in Tel Aviv, Israel caters to the migrant population that congregates there. It is constructed to be open to all, a conscious decision to ensure free and equitable access to the library. Playgrounds for Refugee Children in Bar Elias, Lebanon by CatalyticAction was created as an effort to address the psychological trauma experienced by migrant children and to ensure their healthy development.

The Rohingya refugee population in Bangladesh is one of the largest refugee populations in the world. In 2017, there were 1.2 million people in need of humanitarian aid. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described the situation as “the world’s fastest-developing refugee emergency and a humanitarian and human rights nightmare.” Kutupalong settlement in Cox’s Bazar, near the Bangladesh-Myanmar border is home to these refugees but at the same time is also one of the poorest districts of Bangladesh. The recent influx of Rohingya refugees and haphazard construction of sprawling camps roused local concerns: both communities are competing for resources and there has been widespread destruction of forests and agricultural land, and a related surge in inflation of everything from food to housing prices. About 85% of the host community don’t feel safe with the Rohingya community nearby.

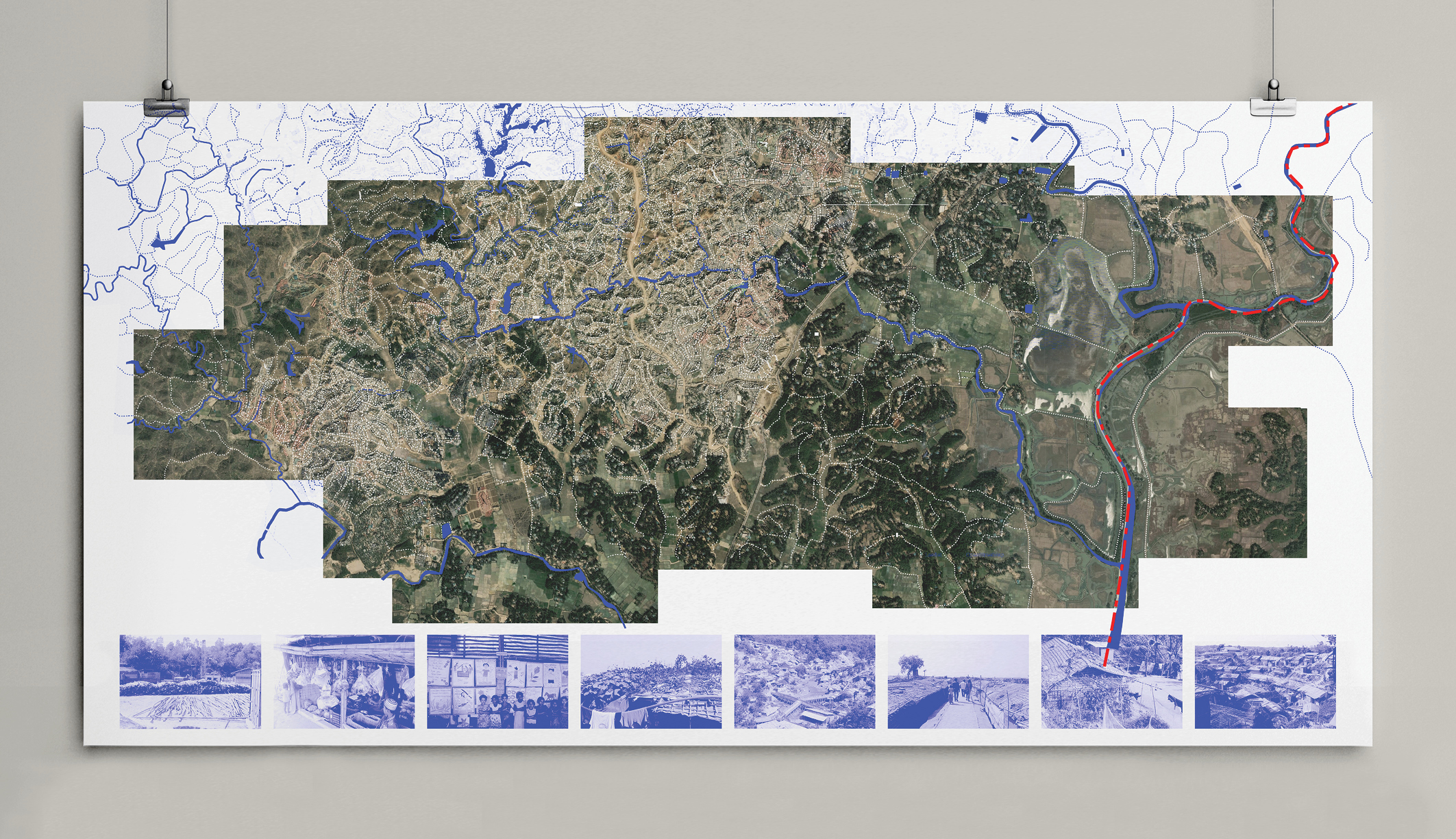

Pamphlet showing the end product of Speculative City seminar for “Redefining the Refugee City” satellite image showing Kutupalong camp 18 and 19 of Kutupalong Rohingya camp

Apart from friction with the host communities, these migrant workers have to face many issues like no access to formal education or prospects of jobs to earn a livelihood, badly constructed shack houses which are not resilient to rain or heat waves, easy access to drugs and violence, rising trafficking due to overpopulation, lack of resources such as water and nutritious food. Mental health is another factor affecting the migrant communities, as many Rohingyans feel hopeless of any positive change in their livelihoods and want to return to Myanmar in spite of the violence they faced there.

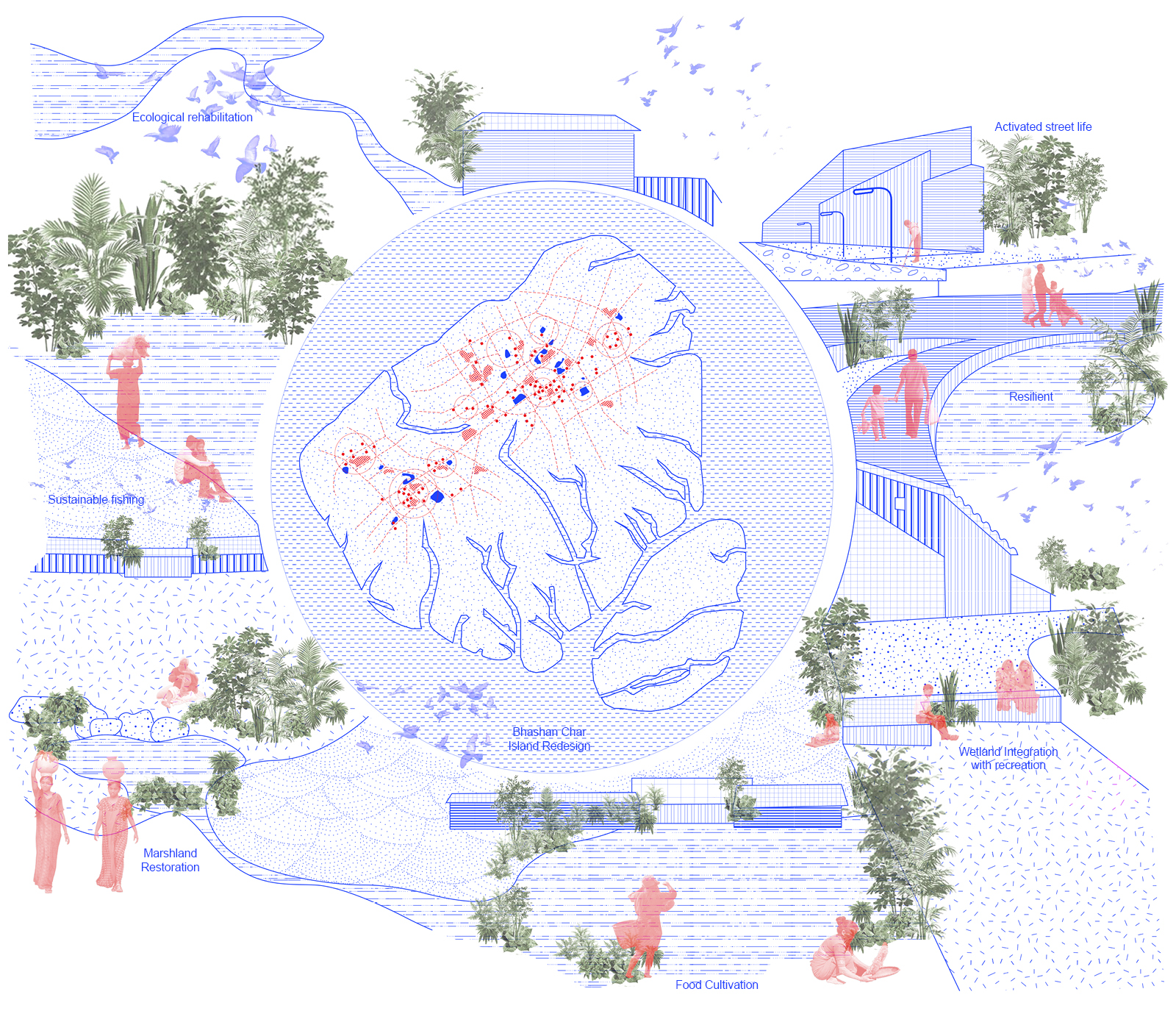

Vision of Kutupalong camp in Bhashan Char Island as pilot for a redefined Refugee City

The Bangladesh government’s solution for this overgrowing crisis is Bhashan Char, an island off the coast of Cox’s Bazar. They have approved plans for a ‘refugee island’ to relocate these refugees. Currently the plans include row concrete housing in a flood prone island with no scope for employment or education. Many Rohingyan’s are wary of this relocation and are rejecting the move as it feels like an island Prison sentence.

Refugee camps have become associated with human suffering, and the sheer size of these settlements testifies to the severity of forced displacement around the world. Yet, these settlements are also spaces of hope and optimism. For many inhabitants, these camps could represent a stepping stone on the path to safety and prosperity.

So what makes a refugee city? By Speculating the city to be a catalyst for promoting the humanity of the migrants that live in it, designing spaces that foster a safe environment which has the capacity to lessen the trauma inflicted by displacement. On a systemic level, the city should pop-up with ease and speed, but also have scope for incrementality. There should be scope to replace temporary elements with permanent ones over time. Diluting thresholds can help in seamless flow of spaces to accommodate equitable access to non-private areas. Refugee encampments and detention centers should no longer act as zones of exclusion, ignored by both governments and civic institutions. On an Urban level, the city should have spaces for congregations. These liminal spaces can vary from smaller ones, adapting to smaller collections of people to large spaces, accommodating more people to collect. This provision will affect mental health by fostering conversations which can give rise to a sense of identity. On a built level the city can be made of structures that are dynamic and changing with the intended use. These built spaces should be well connected with comfortable circulation channels. Landmarking in the city can also help in creating a sense of identity and relationship to the new place. On a human level the spaces of the city should nurture the rights of the individual. They should foster collectives. There can be bodies of stewards from the migrant community which creates a system of social capital in which people can perform tasks in return for benefits. This locally created currency can create an ecology of resources that are circulated within the people of the community.

These speculations when applied to the Bhashan Char Rohingya Refugee island can foster a community which is hopeful and positive of its future livelihood. The city would be built with ecological rehabilitation by marshland restoration. The people would be able to cultivate their own food by farming and sustainable fishing. They would have recreational spaces for congregation, created by wetland integration. This resilient city with its activated street life would thrive with the help of stewards and their social currency.

It is critical for us to speculate such habitable spaces for the migrant populations and respond to the social integration of people with each other. Encourage a sense of belonging and identity by creating socio-cultural bonds amongst the people. These cities are dynamic and should adapt to the changing nature of factors that affect it. Once the communities thrive we further their social fabric by integrating them to the host communities. We need to stop seeing these “refugee settlements” as “camps’, but as the next ‘cities’ and centres of vibrancy by Redefining the Refugee City

Refugee camps have become associated with human suffering, and the sheer size of these settlements testifies to the severity of forced displacement around the world. Yet, these settlements are also spaces of hope and optimism. For many inhabitants, these camps could represent a stepping stone on the path to safety and prosperity.

So what makes a refugee city? By Speculating the city to be a catalyst for promoting the humanity of the migrants that live in it, designing spaces that foster a safe environment which has the capacity to lessen the trauma inflicted by displacement. On a systemic level, the city should pop-up with ease and speed, but also have scope for incrementality. There should be scope to replace temporary elements with permanent ones over time. Diluting thresholds can help in seamless flow of spaces to accommodate equitable access to non-private areas. Refugee encampments and detention centers should no longer act as zones of exclusion, ignored by both governments and civic institutions. On an Urban level, the city should have spaces for congregations. These liminal spaces can vary from smaller ones, adapting to smaller collections of people to large spaces, accommodating more people to collect. This provision will affect mental health by fostering conversations which can give rise to a sense of identity. On a built level the city can be made of structures that are dynamic and changing with the intended use. These built spaces should be well connected with comfortable circulation channels. Landmarking in the city can also help in creating a sense of identity and relationship to the new place. On a human level the spaces of the city should nurture the rights of the individual. They should foster collectives. There can be bodies of stewards from the migrant community which creates a system of social capital in which people can perform tasks in return for benefits. This locally created currency can create an ecology of resources that are circulated within the people of the community.

These speculations when applied to the Bhashan Char Rohingya Refugee island can foster a community which is hopeful and positive of its future livelihood. The city would be built with ecological rehabilitation by marshland restoration. The people would be able to cultivate their own food by farming and sustainable fishing. They would have recreational spaces for congregation, created by wetland integration. This resilient city with its activated street life would thrive with the help of stewards and their social currency.

It is critical for us to speculate such habitable spaces for the migrant populations and respond to the social integration of people with each other. Encourage a sense of belonging and identity by creating socio-cultural bonds amongst the people. These cities are dynamic and should adapt to the changing nature of factors that affect it. Once the communities thrive we further their social fabric by integrating them to the host communities. We need to stop seeing these “refugee settlements” as “camps’, but as the next ‘cities’ and centres of vibrancy by Redefining the Refugee City